Artists have continually reimaged the human figure. While some have followed tradition and others have rebelled against it, all share the same desire to grapple with questions surrounding the universality of the human experience. Spanning modernist to contemporary works, this exhibition charts a history of artistic engagement with figuration.

The end of the 19th century beckoned in the Modern age with artists seeking new perspectives on the figure. With the rise of abstraction in the 1900s, interest in the figure was rejuvenated as an act of revolt. Rejecting the idea that referencing the physical world was unnecessary, artists took the body as a starting point for their interpretations. Recently, a new focus on figuration has emerged, anchored on new conceptual shifts. Perpetually reimagined, politicised, contorted, and scrutinised, the human figure is the most fascinating and enduring of subjects.

-

-

Modernism: a new tradition of figuration

At the turn of the 20th century, new styles of figuration emerged. While the body itself, and in particular the nude, was a classical subject matter sanctioned by the Academy, artists rebelled against the way in which it was depicted.

For the Impressionists, a looser paint application allowed them to re-address the body. Although Renoir took inspiration from Ruben’s bountiful nudes, his use of expressive brushwork was purely modern. He described in his own words how his great desire was for “skin that caught the light well”.

There was also a shift in who was a fitting subject. The Impressionists used their friends, acquaintances and those on the fringes of popular society to be the subject of their paintings beyond professional models.

-

Available works

-

-

Available works

-

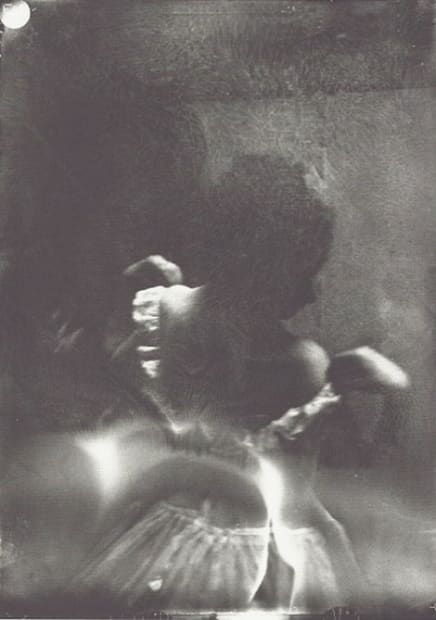

Edgar Degas, Danse Espagnole, c.1885

Edgar Degas, Danse Espagnole, c.1885 -

Henri Matisse, Petite Tête aux cheveux striés, 1906-1907

Henri Matisse, Petite Tête aux cheveux striés, 1906-1907 -

Auguste RodinL'éternel printemps, second état, 4ème réduction, dite aussi "no.2'", 1884Bronze

Auguste RodinL'éternel printemps, second état, 4ème réduction, dite aussi "no.2'", 1884Bronze

This reduction was conceived in 1898 and cast by the Alexis Rudier foundry in 19279 3/4 x 13 x 7 7/8 in, 24.7 x 33 x 20 cmInscribed 'Rodin', stamped with foundry mark and stamped with raised signature 'A. Rodin'

-

-

-

Cubism and the new geometry

Led by Picasso and Braque, the Cubist movement created an entirely new visual language. They rejected traditional rules of perspective and conventions for the representation of form, instead creating multiple planes of vision within a single artwork.

Louis Vauxcelles, a contemporary critic known for having given Fauvism its name, described the work of Braque in the 1909 Salon des Indépendants as “bizarreries cubiques”, or ‘cubic oddities’, thence titling the movement.

Cubism soon caught the imagination of many Modernists. Marcoussis and Archipenko joined the larger Cubist circle of La Section d’Or alongside Leger, Delaunay and Laurencin, with their work and subsequent Salons bringing Synthetic Cubism to the attention of a wider audience.

These artists demonstrated how the figure could be reimagined formally and conceptually, subverting the traditional subject matter such as the nude. This innovative approach paved the way for a plethora of reinterpretations of the human form. Cubism influenced artists for generations to come to experiment with the possibilities of line, volume and vision.

-

Available works

-

-

Available works

-

Sculpting form

Henry Moore and Baltasar Lobo -

Following the Cubists, a number of sculptors sought individualised perceptions of the figure. Henry Moore, in an approach called ‘direct carving’, worked by hand to mould his materials to his own personal visual language. Influenced by Surrealism, Moore’s natural forms morphed into figures with abstracted spaces within. He tried, in his own words, “to become conscious of space in the sculpture”, negative space became a shape in its own right. Moore and his contemporaries later returned to casting in bronze, attracted by the freedom and uniformity that it offered.

Baltasar Lobo took inspiration from Cycladic art to reduce the figure to its most elemental. Largely interpreting the female figure, he used tactile surfaces to create highly sensual works. His application of subtly patinated smooth bronze and Carrara marble all add to the sensation of the surface as skin.

-

Available works

-

Henry Moore, Maquette for Reclining Figure, Conceived in 1945

Henry Moore, Maquette for Reclining Figure, Conceived in 1945 -

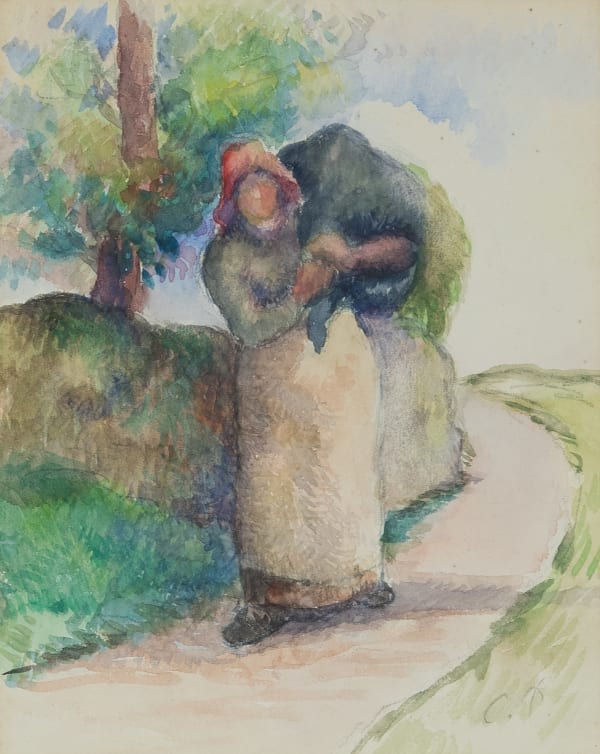

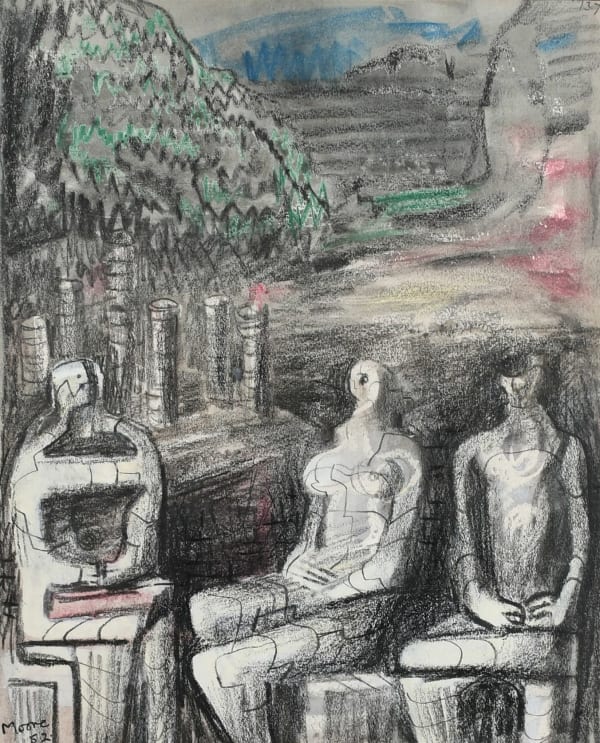

Henry Moore, Three Figures Seated In a Landscape, 1950-51

Henry Moore, Three Figures Seated In a Landscape, 1950-51 -

Baltasar Lobo, Torse penché dans l'espace, 1970

Baltasar Lobo, Torse penché dans l'espace, 1970 -

Baltasar LoboOberstdorf, 1969Marble18 1/8 x 10 5/8 x 5 1/2 in, 46 x 27 x 14 cmSigned 'Lobo'

Baltasar LoboOberstdorf, 1969Marble18 1/8 x 10 5/8 x 5 1/2 in, 46 x 27 x 14 cmSigned 'Lobo'

-

Henry MooreTeatime, 1981Ballpoint pen, wax crayon, gouache, watercolour wash on T.H. Saunders watercolour paper5 1/2 x 5 1/8 in, 14 x 13 cmSigned 'Moore' lower leftSold

Henry MooreTeatime, 1981Ballpoint pen, wax crayon, gouache, watercolour wash on T.H. Saunders watercolour paper5 1/2 x 5 1/8 in, 14 x 13 cmSigned 'Moore' lower leftSold -

Henry MooreSemi-Seated Mother and Child, c.1981Bronze

Henry MooreSemi-Seated Mother and Child, c.1981Bronze

Edition 2 of 9 cast by the Fiorini Foundry, London5 1/2 x 7 3/4 x 4 3/4 in, 14 x 19.7 x 12 cmInscribed with the artist's signature and numberedSold

-

-

-

Available works

-

Contemporary Figuration

There has been a renewed focus on figuration in recent years. Ownership of one’s image, the gaze, physicality, and the meaning of being human have been called to question. Self-portraiture lends itself to a greater level of introspection, as artists use their image to address psychological and societal issues.

Artists such as Shani Rhys James uses self-portraiture as a means to question female stereotypes and the performative art of dress.

-

Available works

-

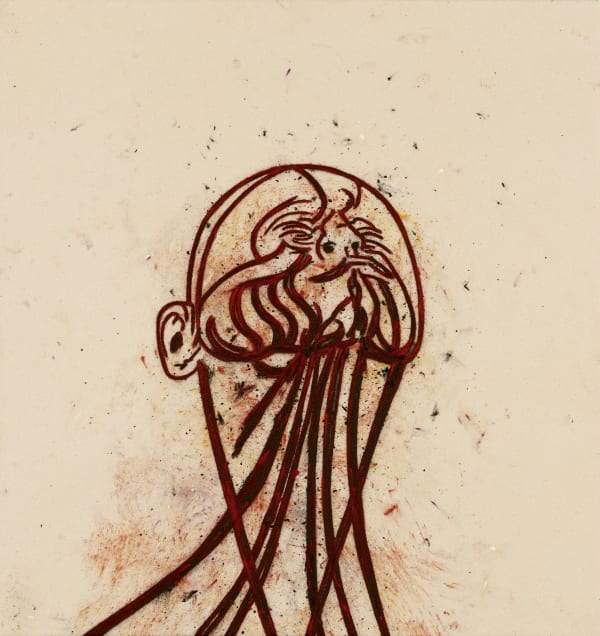

TONY BEVAN

Self Portrait after Messerschmidt (PC108), 2010

Signed twice and inscribed twice 'Bevan PC108' on the reverseAcrylic and charcoal on canvas93.7 x 88.9 cm; (36 7/8 x 35 in.) -

Howard Hodgkin, Untitled (After Lunch), 1981

Howard Hodgkin, Untitled (After Lunch), 1981 -

Shani Rhys JamesStudio Head, 2010Oil on gesso board11 3/4 x 9 7/8 in, 30 x 25 cmSigned verso

Shani Rhys JamesStudio Head, 2010Oil on gesso board11 3/4 x 9 7/8 in, 30 x 25 cmSigned verso

-

-